We Architected CockroachDB the Wrong Way (And It Works Better)

Disclaimer: This is likely a bad idea. We're probably missing something obvious. Smarter engineers would find a better solution. But here we are.

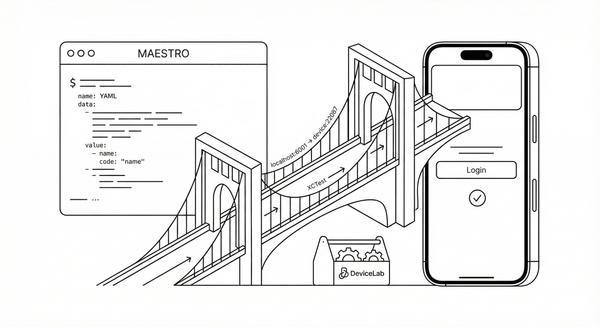

When we started evaluating CockroachDB for DeviceLab, we had high hopes. The promise of a distributed SQL database that could scale horizontally while maintaining consistency seemed perfect for our SaaS platform. After all, who doesn't want the scalability of NoSQL with the familiarity of PostgreSQL?

But then reality hit us like a poorly configured database timeout.

The Journey Into Madness

Our first attempt was with CockroachDB's cloud offering. Simple queries were taking over 2 seconds. Table creation? Nearly 2 minutes. We raised a support ticket, hoping for some magical configuration fix. Instead, we got two responses that made us question everything. First, they suggested deleting our entire cluster and starting fresh. When that didn't work, they essentially told us that performance issues weren't really issues unless something was completely "broken."

We thought maybe we were doing something wrong, so we decided to run our own tests. That's when things got weird.

We spun up CockroachDB on Google Cloud (GCE) and ran the same queries. They completed in 200 milliseconds. Better, but still not great. Then we tested a single-node CockroachDB instance on a tiny VM with just 2 vCPUs and 2GB RAM. The same queries? 20 milliseconds.

How was a resource-constrained single node outperforming a properly provisioned cluster by an order of magnitude?

When Physics Stopped Making Sense

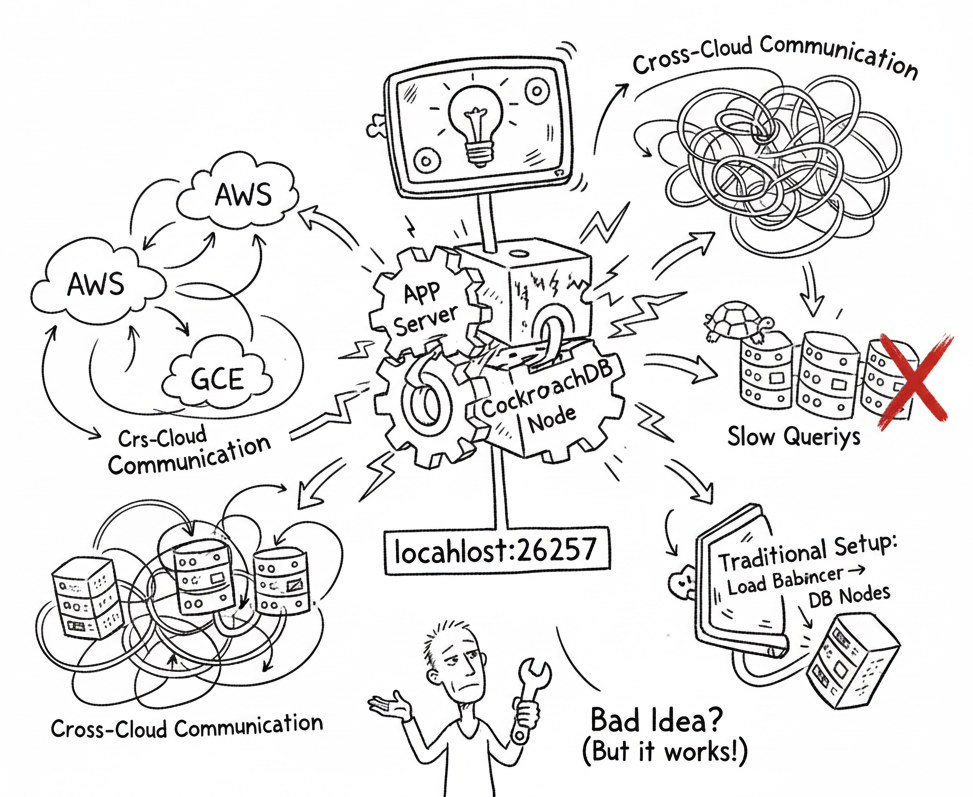

The real head-scratcher came when we tested cross-region connectivity. We had application servers on AWS and a database cluster on GCE. Logic would suggest that keeping everything within the same cloud provider and region would be faster, right?

Wrong.

Our server on AWS connecting to GCE database took 124 milliseconds for queries. The same server moved to GCE, connecting to a database in the same region, took 2.65 seconds. Yes, you read that correctly. Cross-cloud communication was literally 20 times faster than same-region communication within GCE.

At this point, we started questioning our understanding of basic networking. Maybe we were measuring wrong? Maybe we had misconfigured something fundamental? We ran the tests again. And again. The results were consistent.

The Multi-Node Penalty

As we dug deeper, we discovered something that should have been obvious in hindsight: CockroachDB's distributed nature comes with a cost. Every write needs consensus from the majority of nodes. Every query might need to hop between nodes to find the leaseholder for the data. The more nodes we added, the slower things got.

This makes sense for CockroachDB's intended use case - globally distributed applications where surviving region failures is more important than raw speed. But for our use case, where most customers are regional and latency matters more than multi-region survival, we were paying a heavy price for benefits we didn't need.

The Lazy Solution

Now, a competent engineering team would have taken this learning and designed a proper architecture. They might have implemented intelligent query routing, or used read replicas, or maybe even questioned whether CockroachDB was the right choice at all.

We are not that team.

Instead, we looked at our application servers sitting there using 150MB of RAM and less than 10% CPU (after 10 years of optimization, our server is embarrassingly efficient), and we looked at our database nodes needing dedicated instances, and we had a terrible, horrible, no-good idea.

What if we just... put them together?

The Setup Nobody Should Copy

So that's what we did. Each of our instances now runs both our application server and a CockroachDB node. The application connects to localhost:26257. That's it. That's our entire database architecture.

We know this violates every principle of proper system design. Separation of concerns? Thrown out the window. Independent scaling? Not possible. Maintenance windows? They affect everything. Any architect looking at our setup would immediately fail us in a design review.

But here's the embarrassing truth: it works better than our "proper" setup did.

When our application makes a query, one of three things happens. If the data's leaseholder is on the local node, we get sub-millisecond response times. No network hop at all. If the leaseholder is on another node, our local CockroachDB forwards the request - one network hop. Compare this to the traditional setup where you'd go from app server to load balancer to a random CockroachDB node which then might forward to the actual leaseholder - potentially two network hops.

On average, we eliminated an entire network round trip from every database query.

Why This Is Still a Bad Idea

Let me be clear: this is probably wrong. We're almost certainly creating problems we haven't discovered yet. Real engineers separate application and database tiers for good reasons that we're too lazy or ignorant to fully appreciate.

Resource competition is theoretically a real concern. Sure, our app barely uses any resources, but what happens during a CockroachDB compaction? Or during a backup? Honestly, we don't know yet. We haven't hit these issues. Maybe we never will. If we do, our solution is already planned: just throw more RAM at it. Hardware is cheap. Thinking is expensive.

We also completely waste CockroachDB's distributed query capabilities. The query optimizer assumes all nodes are equally accessible, but our setup creates artificial preferences that probably confuse its planning. We're using a Ferrari to do grocery runs.

The Economics of Incompetence

The economics actually make more sense than they first appear. What happens when you need to scale?

Traditional setup needs more capacity? You need to figure out whether it's the app tier or the database tier that needs scaling. Then coordinate the changes. Then rebalance your load. Then debug why your connection pooling is suddenly acting weird.

Our setup needs more capacity? We just add another instance. That's it. Need more database nodes for resilience? Add an instance - you get both an app server and a CockroachDB node. Running out of RAM because our app suddenly decides to eat memory like Chrome? Just double it. Still not enough? Double it again. The cost difference is trivial compared to debugging networking issues at 3 AM.

The real kicker? Our single app server can handle 10,000 requests per second (we tested this, though we'll never see that load). So when we add instances, we're really adding them for database distribution, not application capacity. But we get both anyway.

This flexibility is worth more than any marginal infrastructure savings. When everything is the same instance type running the same image, scaling becomes a non-event. No coordination, no complex decisions, no 3 AM debugging sessions trying to figure out why your app servers can't reach your database through the load balancer that someone helpfully reconfigured.

We're essentially trading a bit of infrastructure cost for massive operational simplicity. And given that human time costs more than compute time, we're probably actually saving money.

What We Should Have Done

Looking back, we probably should have just used PostgreSQL with streaming replication. It would have been simpler, faster, and more appropriate for our needs. Or we could have hired someone who actually understands distributed systems to configure CockroachDB properly. Or we could have stuck with the cloud offering and figured out what we were doing wrong.

But we didn't. We took the lazy path, combining things that shouldn't be combined, ignoring best practices that smarter people developed for good reasons.

The worst part? It's been running in production for months without issues. Our P99 latency is better than it ever was with the "proper" setup. Our customers are happy. Our ops burden is minimal.

We keep waiting for it to blow up spectacularly, to teach us the lesson we deserve for our architectural sins. But it keeps working.

Conclusion

I'm not advocating for this approach. Please don't read this and think "those DeviceLab folks are onto something." We're not. We're just lazy engineers who found a local maximum that works for our very specific, probably unusual case.

If your application is tiny, your workload is read-heavy, you're allergic to operational complexity, and you're willing to accept that you're probably doing it wrong - then maybe our terrible setup might work for you too.

But probably not. You should probably do it properly. Unlike us.

P.S. - If you know why this is going to blow up in our faces, please tell us. We're genuinely curious about what we're missing. There has to be something, right?

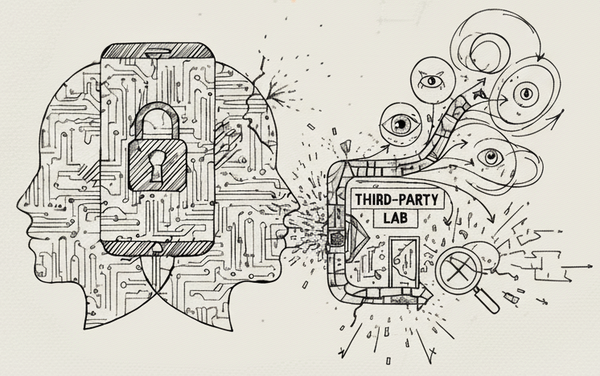

If you're looking for a solution where questionable architecture decisions can't compromise your data, check out DeviceLab we built a zero-trust distributed device lab platform. We don't promise not to look at your data; we architecturally can't. Everything runs on your devices, connected peer-to-peer. Your tests, your data, your security. Unlike our database setup, we actually thought this one through.

*AI was used to help structure this post